A shady verandah protects the earthen walls of this historic pise house in Bedourie, Qld.

Designs on the land

From the salt of the coast to the sands of the desert, the architecture of our nation is as much a function of the landscape as an attempt to live in it.

STORY + PHOTOS ANDREW HULL | OUTBACK MAGAZINE

Dawn is a razor of gold slicing across the rangelands of western NSW. As the great globe of the sun commences its inevitable arc, the broader landscape is brought into focus, russet-red and undulating with grey-green smudges of hardy vegetation. The one-time oceanic reef of White Cliffs shimmers unreliably in the shadowland.

Graeme Dowton at home in his underground dugout, White Cliffs, NSW.

Out here in 1992, opal miner, minerals consultant, jeweller, tour operator, cafe owner and barista Graeme Dowton began the process of converting 100-year-old mining operations into somewhere to live. “At the start of the process, I had a wheelbarrow and a shovel, and I started cleaning out the old underground mines so I could see what was left – I had to make sure there were enough columns of earth to support the roof.”

The Serbian Orthodox church in the SA opal mining town of Coober Pedy made extensive use of mining technology to create this vaulted underground space aimed at fostering a different kind of wealth.

To enter his dugout now is to step inside a parallel world of both the strange and the familiar. On one hand, you are inside a cave, with rounded, rough walls and ceilings, odd-shaped passages and doorways. On the other, you are in a home with a dining area, living room or bedroom, with lounges, tables and a flat screen television.

“The walls aren’t flat or straight,” he says. “You punch into old workings, an old hole or mine shaft, and that dictates the floorplan. You can’t really fill it back up again, so you just go with it.”

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: An artist’s impression of the Australian Opal Centre (AOC); AOC CEO Jenni Brammall at the site of the proposed new building; making the best of available resources at the wacky beer-can shack in Lightning Ridge; an imagined garden in the AOC.

Mithaka traditional owner Josh Gorringe at the remarkable gunyahs, possibly the oldest standing structures in Australia.

Inside, the benefits of living underground are instantly identifiable. The hot, volatile air of the Australian summer becomes a cool, still, constant 22°C. The light changes to an LED-illuminated blue, accented by shafts of warm sunlight from overhead vents and light wells, and as you draw deeper into the vault, all external sounds disappear.

In the history of Australia, our various buildings have represented our quest to plant roots even in the most hostile environments. Many structures’ inception, renovation and refurbishment represent the most practical and efficient use of available resources. From the oldest to the newest, our buildings are the physical evidence of our gritty tenacity to hold on, to celebrate, and to do whatever it takes to make our place in this land.

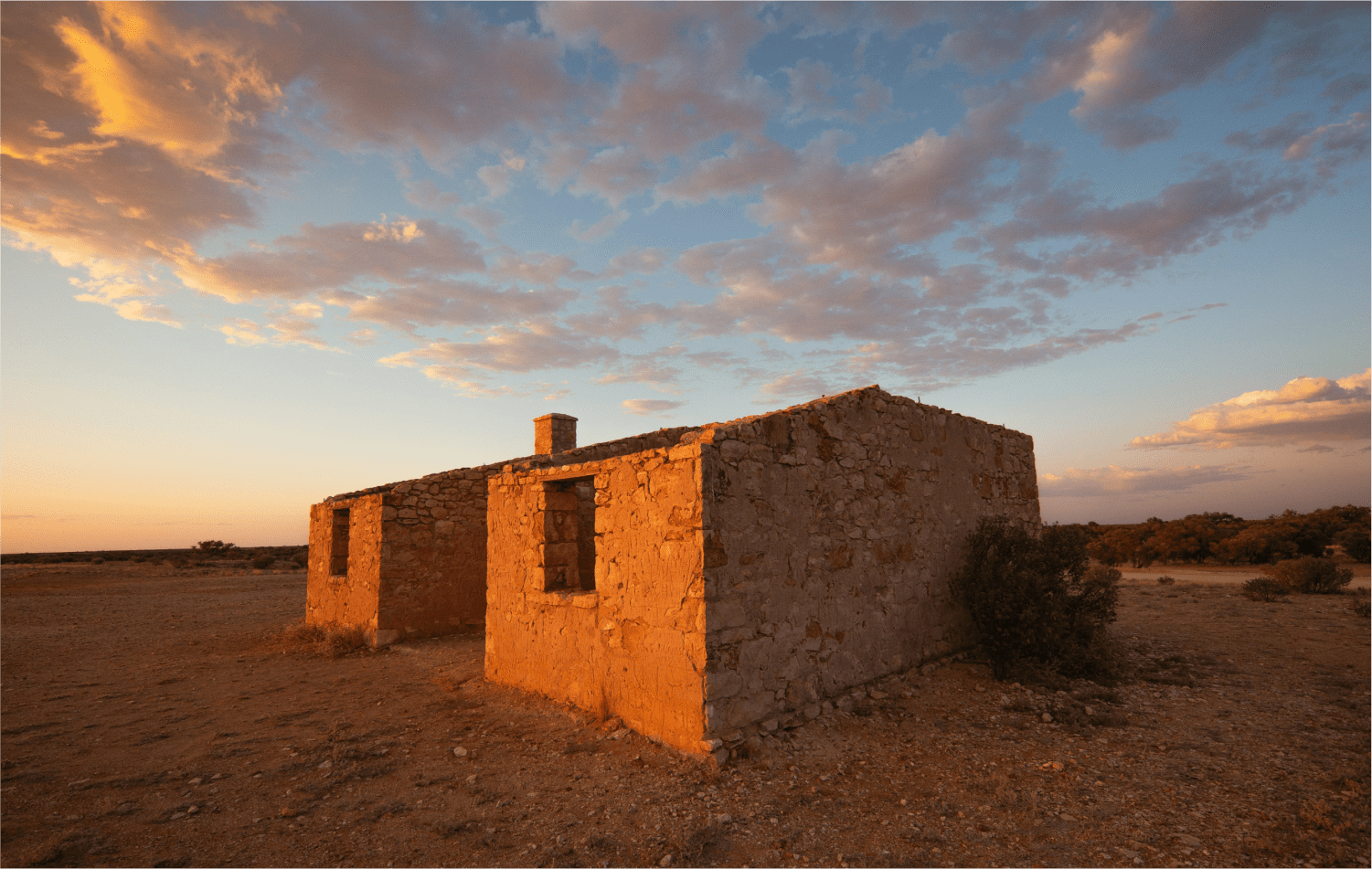

The haunting ruins of Old Carcory Homestead near Birdsville, Qld.

The beautiful Western Lands Building of Bourke, NSW.

Near Birdsville, Qld, on a low rise, sitting resolutely in the blistering outback sun, are what may be the oldest standing dwellings in Australia, the remarkable gunyahs of the Mithaka people. Partly collapsed, but still recognisably structures, these circular dome-like assemblages of gidgee boughs provide a tantalising glimpse into a much deeper history of Australia.

The manor-like Mount Oriel Homestead, better known as Iandra Castle, in Greenethorpe, NSW.

Fred Fry’s hut on the Howqua River, Vic, has provided shelter to generations of high-country campers.

“Being the modern world, we need to use names like ‘house’ because that’s how we explain it,” says Josh Gorringe, general manager of the Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation and traditional custodian of the land and sites. “You’d explain it differently if you had a different cultural framework. Basically they [the gunyahs] are circular with 4–6 main posts – 2 close together for the entrance and 4 more around the edges. Branches were bent over the top in a dome-like arrangement for a roof, and they excavated the interior to create more space and to keep cool.”

Kim Bell-Anderson dips into the raised gardens of the home she and husband Simon built in the Megalong Valley, NSW.

The iconic film set of Craig’s Hut still attracts many visitors to the Victorian high country.

In Bourke, NSW, what is colloquially known as the Western Lands Building, is one of the most interesting and beautiful examples of considered architecture of the late 19th century. The single-storey timber-framed structure of approximately 440sq m floor area is held 1.5m above the ground by extensive brick foundations. With deep verandahs and a high-pitched roofline, the building has been designed as its own air conditioner using the simplest of principles. The ceilings have vents, which allow the air to escape into the roof cavity, where slatted turrets draw the hot air away, like a chimney. The walls have hollow cavities, which extend down to the under-floor, where there used to be large, open water tanks. As the hot air was drawn upwards, so was the cool air from beneath the building, which flowed into the rooms through vents in the walls, keeping the building cool even in the hottest months.

Simon and Kim’s bushfire-resistant house has a fire-proof deck shaded by a shutter-awning that locks down in a fire.

Toowoomba interior designer Angela Smith tends the garden of the classic Queenslander she and husband Bronte have carefully renovated and extended. It is both a much-loved and practical family home, and a source of professional inspiration for her.

In alpine areas, 300 or so mountain huts pepper the tightly squeezed contour lines through the Great Dividing Range in NSW, the ACT, Victoria and Tasmania.

Legendary bushman Fred Fry made his life at the Howqua River, Vic, in the 1940s. His hut is popular among visitors to the Mansfield area, surrounded as it is by broad grassy flats and edged by the pristine mountain stream of the Howqua. The drop slab construction employs hand-hewn timber slabs with the tool marks still clearly visible in places. The roof is probably unique in its assembly, employing alternating logs in a criss-cross elevation to the heavy central beam, with the corrugated iron roofing fastened directly to the beams without rafters or joists.

Time passes, but the impressive municipal buildings of Ballarat continue to tell the story of the city’s community spirit.

The most popular, and perhaps most perfectly sited, of the Victorian huts is perched high up at Clear Hills, near Mt Stirling, with stunning panoramic views towards Mt Cobbler and hundreds of hectares of mountain tops and valleys below. Craig’s Hut was built to replace a set that was constructed for the filming of The Man From Snowy River, after the original hut burnt down. It attracts more than 40,000 visitors every year.

The striking facade of the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery; the design for the 3-storey home of the Ballarat Mechanics Insitute was chosen in 1868.

Bushfires are one of the many challenges that Australian architects face. Simon Anderson tackled the issue head on in the building he designed and built for himself and his partner Kim on their bush block deep in the NSW Megalong Valley in 2015. The angular charcoal-coloured dwelling sits neatly and compactly on the tannish shale of the eucalypt-covered block. “All these walls are actually concrete with insulated layers, and it’s really just a glorified bushfire bunker clad in flame-zone rated decking product,” Simon says. “The awning folds down, the main window shutters slide around, and all the other windows have metal shutters that can roll down and cover the whole building. The roof has a sort of fire blanket built into it in between the layers.”

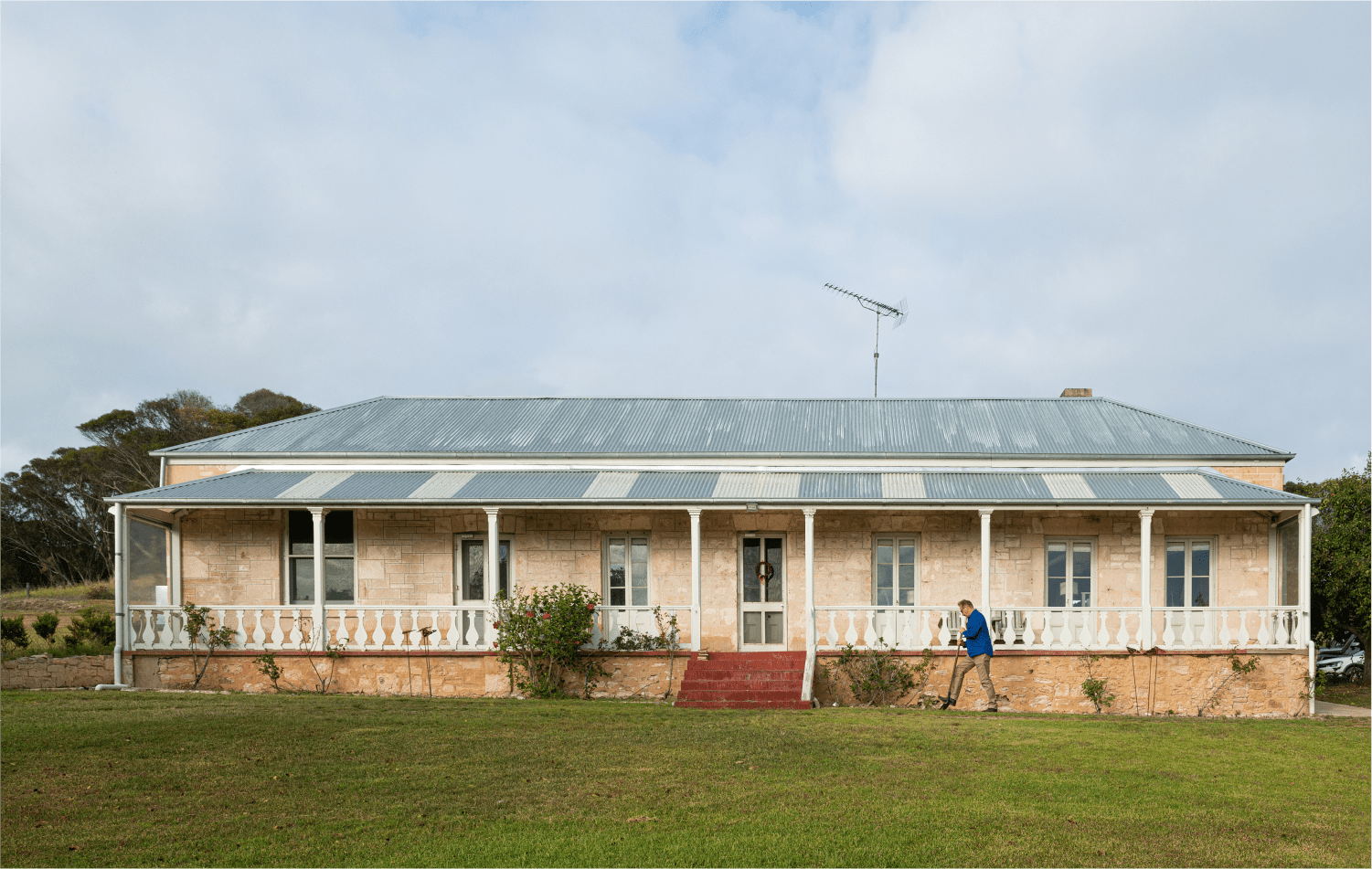

Basil Enright digs the front garden bed at his home – The Hermitage, near Robe in SA. The original limestone structure was built in 1855. Much of the extensive expansions carried out in 1868 were undertaken by Basil’s great-great-grandfather William Savage, an accomplished stonemason.

In subtropical Australia, the Queenslander style of house probably exemplifies the lifestyle. Instantly identifiable, the buildings are typically single-storey houses sitting on raised stumps with relatively low-pitched gabled rooflines, and deep verandahs right around the perimeter.

Ocean House, designed by Rob Mills, sits on Victoria’s Shipwreck Coast and aims to incorporate both the sea in front and the forest behind.

“For me, the ideal Queenslander is a house on stumps, with plenty of room underneath to store stuff and hang your washing if it’s wet,” Queensland building designer Jeff Topping says. “It’s a bit higher than the ground so there are fewer obstacles like fences to block airflow, and if you can get cross-flow ventilation and keep your verandahs open, it’s like wearing a big, wide-brimmed hat.”

In the goldfields of Victoria, Ballarat heritage architect Wendy Jacobs identifies a strong social and civic theme running through some of the most impressive goldfields architecture.

The Shearers Quarters on Bruny Island, Tas, is located on the site of an old shearing shed that was destroyed by fire. Today, is it still used seasonally by shearers and is also rented out as accommodation. According to designers Wardle Studio, the building “transforms along its length to shift the profile of a slender skillion at the western end to a broad gable at the east. The geometry of this shift is carried through the layout of the internal walls, lining boards and window frames”.

The mostly stone and multistorey buildings are predominantly mid- to late-Victorian and early Federation period architecture and, in some cases, seem to strive to outdo each other with bold facades, and ornate stone and render work. “There was a competitive aspect to it, for example, large plate-glass buildings were expensive and difficult to get, so if you had them, you were advertising that you had a bigger, better building and this would be a good place to shop or a good group to join,” Wendy says.

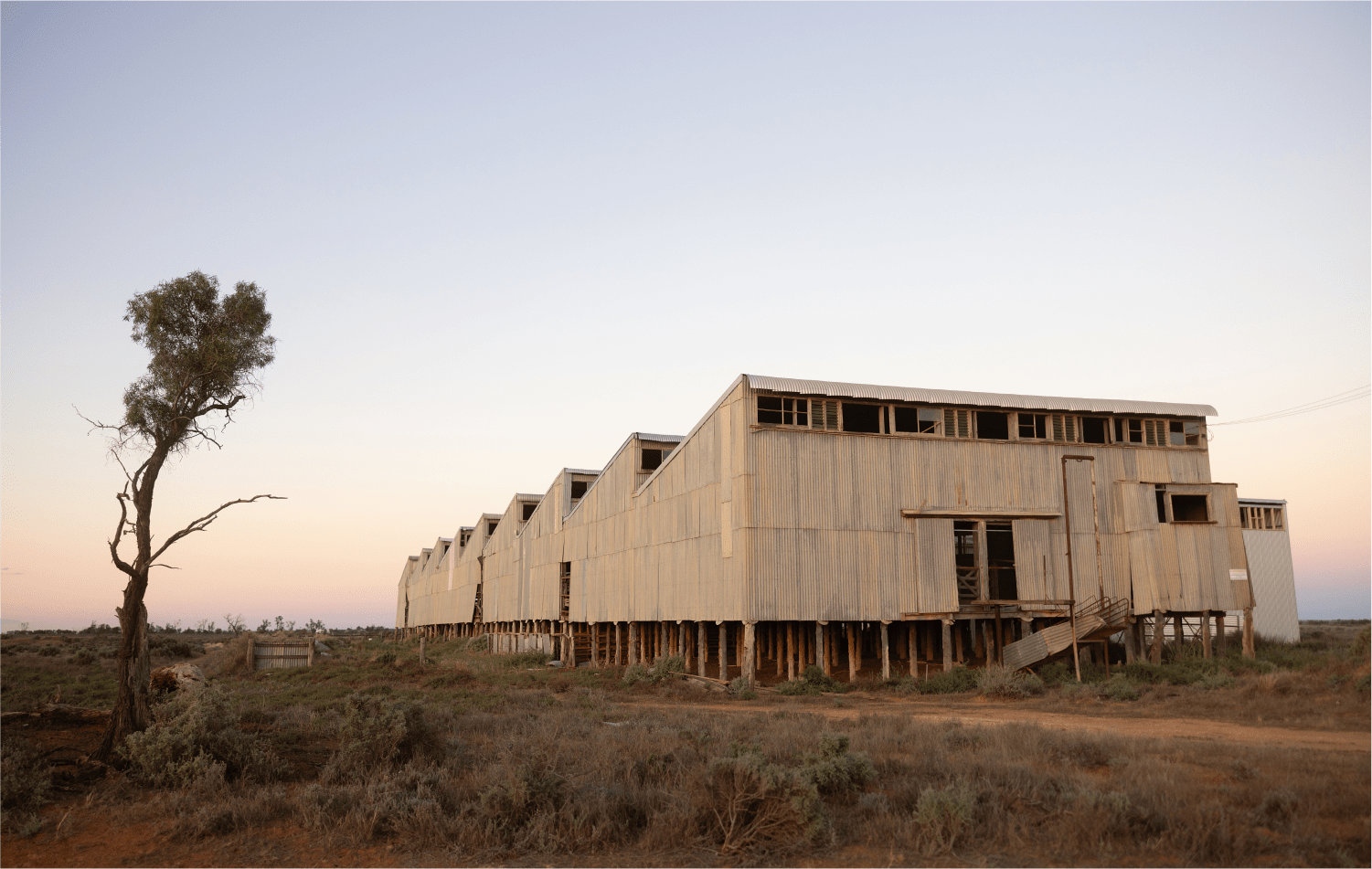

The saw-toothed Nulla Shed in south-western NSW.

Roughly 400km to the west, the prevailing south-westerly winds surge and swirl around the Limestone Coast and the historic fishing village of Robe. Huddled between the mallee-covered low ridge and the coastal lowlands is The Hermitage, a limestone-block building dating back to 1855.

John ‘Basil’ Enright, who has called the house home since the age of 3 says he’ll seek out whichever verandah is sheltered from the winds. “Most coastal houses around here, if they’re well built, will have a couple of decks so that you can escape the wind one way or the other.”

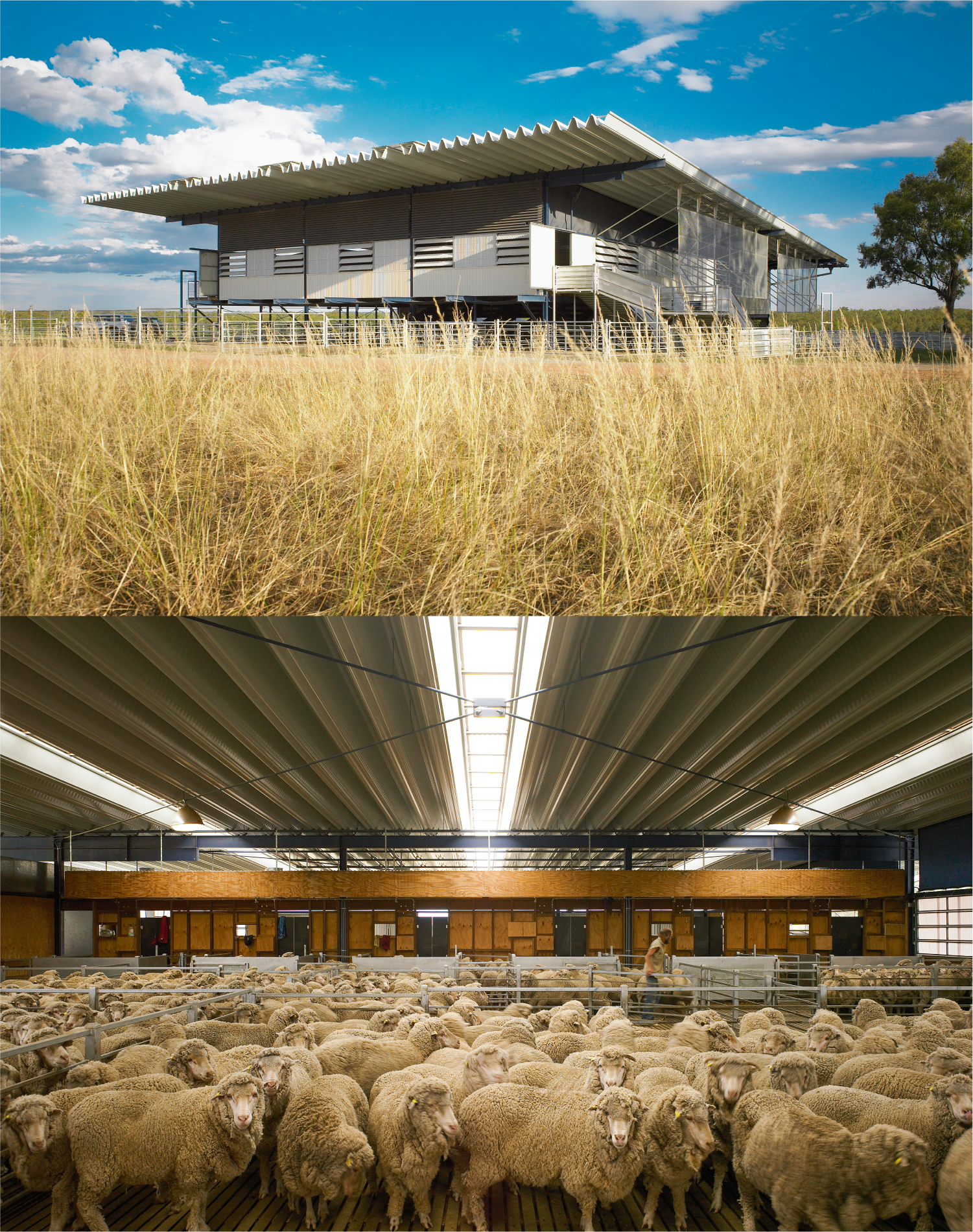

The Deepwater shed on Bulls Run near Wagga Wagga, NSW, has drippers running water down perforated windward-facing steel screens to aid cooling for staff and sheep.

A hallmark of travelling architect Alf Couch’s 1940s designs is the use of curved corrugated iron, as seen here on Wooleen station in WA’s Murchison District.

As Australian architect Max Freeland once said, “A country’s architecture is a near perfect record of its history … Every building explains the time and place in which it was built.”